There has been a lot of interest lately in the transition to minimal footwear. Am I going to get hurt? How long does this transition take? Is this really better for me? Will my old shoes take it personally? Last year at this time, there were 6 minimal shoes on the market. This year there are 64. It’s a hot market, and folks are taking notice. While shoes are nice to talk about, let’s not forget that it’s the runner in the shoe that plays an active role in this equation. Shoes don’t run by themselves!

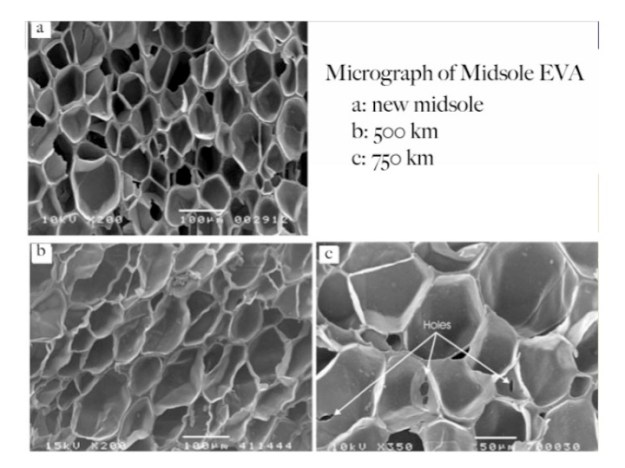

The recent article by Giuliani et. al. has raised some concerns.2 They highlight 2 cases of stress fractures in 2 different runners who transition to minimal footwear. The switch to minimal footwear can be dramatic. You get more “feel” since the squishy midsole is reduced or gone. You get a lower differential from your rear foot to your forefoot. These 2 factors change a) the position of the foot (Heel isn’t higher than the forefoot in full contact) and, b) the demand of the runner to stabilize the foot inside the shoe. In short, with less “stuff” in between you and the ground, you need your body to do a bit more, and get accommodate to a bit more as well.

Ever hear about the experiment with pre-K kids with the cookies? They put a kid in a room with cookie on the table and tell him/her that they can eat the cookie and they’ll get one cookie. BUT, if they don’t eat the cookie, they’ll get 2 cookies later (yea!). The tester walks out of the room and the kids go into panic mode when sitting in front of this stellar, delicious cookie. Most eat the single cookie for instant gratification. They fail to see the merits of waiting patiently for a better result.

What in the world do cookies have to do with running shoes? A lot. The switch to minimal footwear can pay off in the long run, but you need ensure you’ve got what it takes for a successful transition. Obviously any time you make a change to your body, there is an adaptation period that needs to occur. A lot of “experts” say that it will take 6 months to a year to fully transition to a minimal shoe. I’d like to think that this is overly cautious, and like to discuss why using the anatomy. We’ve found great success using the following 3 criteria for runners looking to run with “less”.

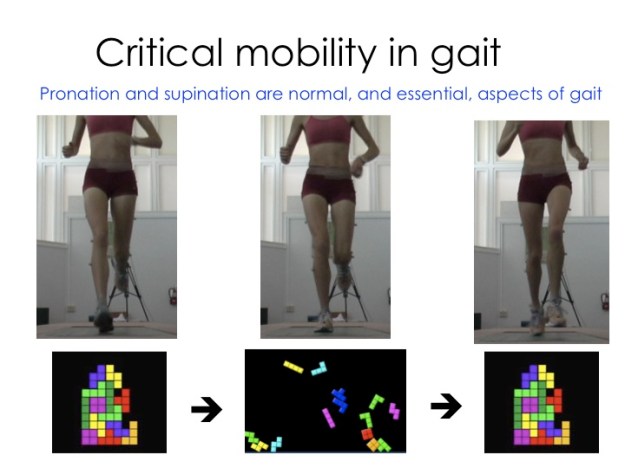

1. Mobility: Traditional running shoes have about a 10-13mm drop from the heel to the forefoot. This creates a “rocker” effect in the shoe. Take a look at a shoe from the side and you’ll see that the curve from the ball of the foot to the tip of the toe rises up. Since your foot is flat, you need to ensure that you have enough mobility (called dorsiflexion) of the big toe to allow the foot to roll over. Additionally, since the heel is higher in a traditional running shoe (think a small high heel) the heel chords are used to operating in a shortened position. You need to ensure that you’ve got the mobility needed to allow the heel chords to operate form their slightly lengthened position. So what to you test?

- Ankle mobility (heel chords) – you need to be able to dorsiflex (cock the foot up towards the shin) about 25 degrees. Lack of mobility here means you’ll need to stretch the calf and Achilles.

- Plantar facsia mobility – with the ankle in about 5 degrees of dorsiflexion, you need to have 30 degrees of dorsiflexion at the big toe. If you don’t have this, you can’t roll over the toes, and will be forced to spin off of the forefoot.

2. Single-leg Standing Balance: normal balance has been identified as standing on single leg for 30 seconds

with a still upper body and full foot contact. Since the midstance phase of running is essentially a single leg squat, it is essential that the runner is able to maintain the foot in contact. A triangle between the inside ball of the foot (1st MTP), end of the big toe (distal phalanx of the 1st ray), and outside ball of the foot (5th MTP) should be seen. When in single leg stance, the muscles in the foot need to be “pro-active” not “re-active”. If you are wobbling your foot back and forth when standing on one foot, you’ve got some room to improve your “proprioception” – or sense of where and what you’re your foot is doing during contact. The most successful way to improve single leg balance is to perform it frequently (15-20 times a day) for small doses (30 seconds each).

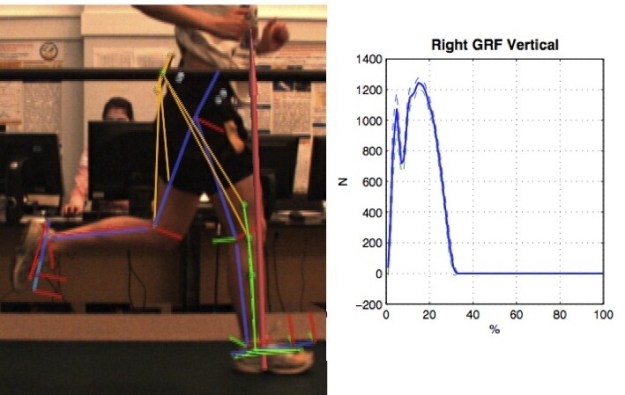

3. Ability to isolate the Flexor Hallucis Brevis: a key factor that distinguishes humans from primates is our medial longitudinal arch. This arch is actively stabilized by the flexor hallicus brevius (FHB). While standing, try to drive the big toe (1st MTP) into the ground (plantar flexion) while slightly elevating (dorsiflexing) the lesser toes. Make sure not to roll the ankle in or out. This test enables screening of muscles inside the foot that stabilize the arch. The FHB can be easily distinguished from the longus (FHL), as the FHL crosses another joint in your big toe (1st IP joint), resulting in your big toe curling. Spend some time getting to know your foot. Aim to drive the big toe down while lifting the little toes (without curling the big toe!), and lift the big toe up while driving the little toes down. It’s the best way to work on coordination of muscles that actively stabilize the foot in stance. It’s your foot – control it! If you can do this, it’s a sign that you can keep the rear foot stable on the forefoot when the body sees the greatest amount of pronation (which is just slightly after midstance and AFTER the heel is off of the ground by the way.)1 Midstance is when forces are highest throughout the body- about 2.5x’s your body weight. You need the internal strength to be able to respond to these forces to keep things in alignment.

When your foot “works” it can actively stabilize the transfer of forces through the foot. If you don’t pass these 3 tests, no worry -get to work on improving your limitations. Pay a visit to your local PT if you need help with specific exercises and stretches to improve. If you lack mobility, research shows it takes 10-12 weeks to gain significant improvements. So stretching for 2 weeks likely won’t be enough for most folks. Improving tissue length can take some time. If your limitations are in the balance aspect, you’ll be amazed how quickly this improves if you simply practice practice practice. Typically, about 2 weeks yields a significant improvement. Finally, strength gains take about 6-8 weeks to achieve. So if you really have trouble isolating your foot muscles, this could take a bit to get them stronger – but you can always improve the strength of your muscles! Passing these 3 tests doesn’t mean that you should go run a marathon in your new minimal shoes on day 1, but we’ve seen that folks who master these have little to no problem making the transition. I’ll note here that these tests are not new in my mind. I’d like all runners – even those who run in traditional shoes – to pass these tests. Its that when the “stuff” under your foot is less, these traits are that much more important.

So invest some time to improve your foot – Because it’s always better to have 2 cookies instead of one! Shoes make a difference, but it’s the runner in the shoe that you’ve got control over.

References:

Dicharry, JM., Franz, JR., Della Croce, U., Wilder, RP., O’Riley, P., Kerrigan, DC. Differences in Static and Dynamic Measures in Evaluation of Talonavicular Mobility in Gait. J Orthop Sport Phys Ther 2009;39(8):628-634

Giuliani J, Masini B, Alitz C, Owens BD. Barefoot-simulating Footwear Associated With Metatarsal Stress Injury in 2 Runners. Orthopedics. 2011 Jul 7;34(7)