Yesterday we briefly discussed the idea of loading rate, and why it matters to you as a runner. Today we’ll talk of the 3 primary ways runners can change loading rate, and likely dispel some myths while doing so. If I ruffle some feathers while doing this, don’t get frustrated. Its good to stretch you brain. Let’s look at what we do know about loading rate, and what is a bit fuzzy.

Methods to decrease loading rate involve a combination of:

- A foot contact style closer to the body’s center of mass

- Minimizing excessive lumbar extension (which shifts the body’s center of mass posterior in relation to foot contact)

- Changing limb stiffness through feedback training.

****Warning – some of this gets a bit tedious, but there has been a lot of request for this information lately, so lets dive in shall we?

Let’s get right to the hot topic. Should you land on you forefoot, midfoot, or rearfoot?

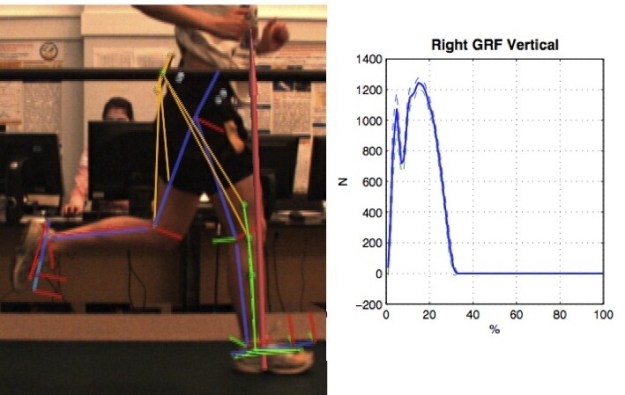

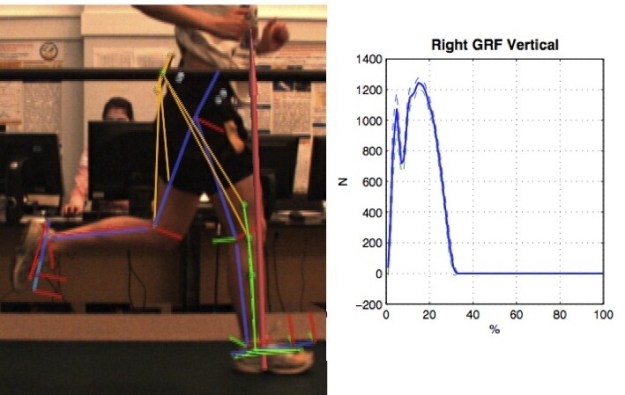

Right below, is a graph of a runner landing with a midfoot gait. You’ll notice a very distinct impact peak (first bump) and a larger active peak (second bump). You’ll also notice that the slope of the first bump (from the x-axis to the top of the first bump) is quite steep.

What kind of foot contact pattern made this graph? Nope – not a heel striker – but a midfoot striker. In fact this woman is about as midfoot as possible – her foot came down completely flat down at contact. I know ….this runs counter to a lot you’ve been told right? Hold on – let’s keep going.

Now look at runner #2’s graph. Notice the single mountain (or peak). Notice that the slope of the line from contact to peak is quite less steep than that of Runner #1. A LOWER loading rate! Guess what kind of contact style this runner utilized? A heel-strike. Yes. You read that right. A heel striker had a lower loading rate than a midfoot striker …..in this situation.

What gives? The media tries to make things simple. They say that “mid-foot” or “forefoot” is better than rearfoot. I love reading running forums where people with way too much time on their hands armchair quarterback running styles. They look at a picture or video of a contact pattern of some guy running across the screen and say “wow – nice midfoot strike –that runner is efficient.” They don’t know who the runner is, or what his time was for the race. They just saw a foot strike and proclaimed him efficient. Then they’ll scroll down and see some picture or video of some guy heel striking and proclaim that he/she is an “in-efficient” runner based on the heel strike. This “in-efficient” runner might be an in-efficient runner. Or it might be Meb Keflezighi (a runner who is just a bit faster and more efficient and than most of your reading this post). You see, these arm chair-quarterbacks aren’t very good at identifying efficient gait. Fancy force plates are. I do this for a living and still need data from my lab to give me the answer because no one can actually see forces. So what have we learned from these fancy force plates? Its NOT rear-foot or midfoot or forefoot that matters – its where the foot contacts in relation to the body’s center of mass.

As I stated above, I picked some outliers just to make a point. It is true that for MOST runners, adopting a midfoot or forefoot gait style will lead to decreased loading rates. However, its not because the foot lands differently, its because a rear-foot style typically allows you to land with the foot farther in front of the body’s center of mass (over-striding). Switching to a contact style that moves the foot closer to the body’s center of mass usually means that we land closer to the font of the foot. But not always. Let’s look at the elite runners to dig a bit deeper.

To run really fast, it’s very simple. You either increase your stride rate or your stride length. Simple right?

- Stride rate- this is also referred to as cadence. Cadence ranges in cycling are pretty variable. Cyclists use anywhere from 45 – 140 rpm in competition, depending on the event and terrain. When we look at running, you’ll notice that cadence for middle distance through marathon distance typically ranges from 88-96 rpm. This is a much narrower effective window than cycling. We’ll look more in depth at cadence in a later post, but for right now, its safe to say at the elite level, there isn’t a huge difference in cadence values.

- Stride length –if cadence values are held fairly consistent, the only other way to run faster is to adopt a longer stride length. The stride length of someone running 4:30 miles is significantly longer than running 7:45 miles. What we see is that a number of the elites land on the rearfoot, but their center of mass is still very high up at the time of contact. When running, you are a projectile in the air with your center of mass following a parabolic curve. So even though the elites often “contact” on their rearfoot, they don’t really have much pressure (force) on it until their center of mass lowers to the ground. This effect produces a low loading rate with a heel contact, and is exactly what occurred in runner #2 above.

So let’s summarize what we’ve said about contact foot contact style. For most runners, landing closer to the body’s center of mass is an effective tool to lower loading rates. Barefoot running, minimalist running, and increasing cadence (faster cadence means you don’t have time for your foot to reach out far in front of the body) are all effective tools to accomplish the end goal of decreasing loading rate. This being said, contact style is NOT the only way to decrease loading rate. Its possible to have lower loading rates with multiple foot contact styles, and other factors as well.

So let’s summarize what we’ve said about contact foot contact style. For most runners, landing closer to the body’s center of mass is an effective tool to lower loading rates. Barefoot running, minimalist running, and increasing cadence (faster cadence means you don’t have time for your foot to reach out far in front of the body) are all effective tools to accomplish the end goal of decreasing loading rate. This being said, contact style is NOT the only way to decrease loading rate. Its possible to have lower loading rates with multiple foot contact styles, and other factors as well.

***Note: Unless the person is accelerating, it is not possible to have the foot contact directly under the center of mass. At steady state, the foot does (and should) contact in front of the center of mass.

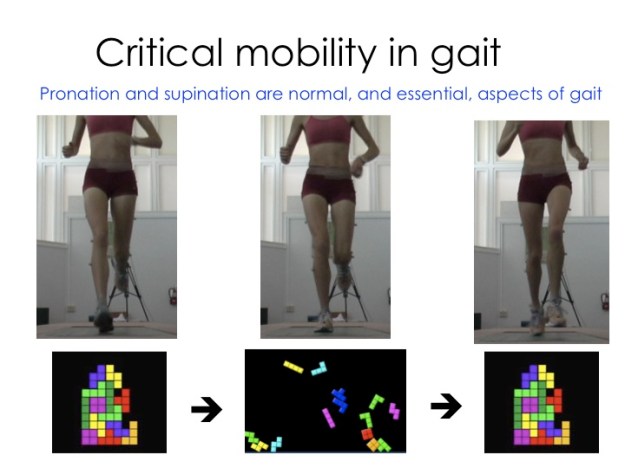

The effect of posture

We said that, in general, a foot contact closer to the center of mass would decrease loading rate. On the flipside, posture can be utilized to alter the center of mass in relation to the foot. Most of us stand, walk, run, etc with poor posture. Take a look at the runner below. The runner is in exactly the same phase of gait, except for a more arched low back on the right than on the left. The posture on the right is typical to most runners. We hang out in the “back seat” with lots of arch in the low back. This change in lumbar position moves our center of mass backwards thus causing our foot to land further in front of the center of mass. Therefore, keeping a neutral lumbar spine (not arched) is essential to keep our center of mass over our foot when running – and has the effect of minimizing loading rate.

Lastly – gait cueing and limb stiffness. Here’s where things come together, but also show need for additional research. In our lab, when we get someone with high loading rates, we show them their ground reaction force plots in real-time as they run, and ask them to change it. Normally, we don’t tell them how, we ask them to “play” with their graph shape as they run. Most runners figure out how to minimize their loading rates by getting visual cues, or feedback. This is the best way since the runner is aware of the conscious modifications they are doing to alter their loading rates and can see instant feedback to observe success – thus learning! If they don’t “get it”, we guide them through the technique modification so they can see the effects of their form changes as they run. Again – the goal is to get the runner to retain this sensation so they can alter their gait to make long-term changes to decrease tissue stress. On the simpler side, research has been done that simply told runners to “run soft”. These individuals were found to decrease their loading rates. Gait cueing works. How does it work? People modify their contact style, posture, and their limb stiffness to achieve a desired result. Limb stiffness relates to how compliant the runner maintains the knee to modulate the rise and fall of the center of mass. There is more work to be done here to dig deeper, but this should hopefully answer the bulk of questions for now.

Summary:

What does this mean for you as a runner?

There is mounting evidence that minimizing loading rate has vast implications for a number of injury prevention strategies. There is also mounting work to show links to performance, though this is inconclusive at this time. There is additional work to be done to show how the gait style changes observed with decreased loading rate correspond to improved performance. Another topic for another day……

If you want to try to decrease your loading rate, you need to get your foot to land closer to the body. Barefoot running is a good drill for this since it “forces” you to avoid over-striding. There is evidence that a properly constructed minimal shoe should also lead to minimal loading rates (although no one can say all minimal shoes since the definition of this market sector is so vague). Keep your torso centered over your lower body and avoid the temptation to run in the “back seat”, especially as you fatigue.

Run Tall! Run Soft!

Yup…. Less (loading rate) = More.